Meet Peggy Robinson: The Visionary Behind PEG Gallery in Pōneke Wellington

Interview by Macy Andres

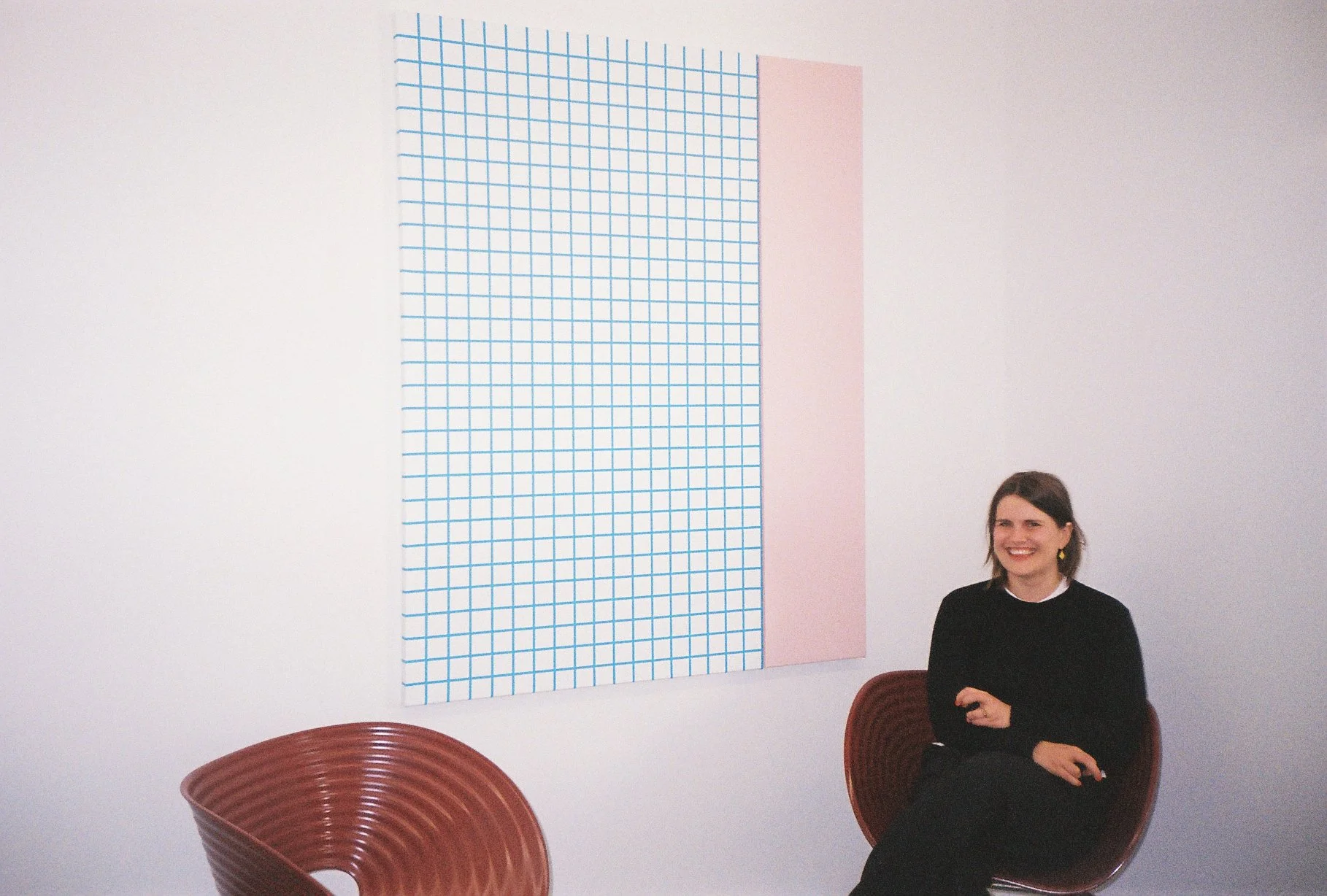

Photographs by Claudia Hall

There is a new kid on Pōneke’s gallery block. After a seven-year tenure at Page Gallery, 29-year old Peggy Robinson has cut the ribbon on her eponymous PEG, a decisive contemporary art gallery located in the heritage A.E. Ivin building on 230 Cuba Street. Forward, benevolent, and joyful are all adjectives befitting the space, which harnesses the kinetics of Pōneke’s burgeoning artists with a poised, careful hand. The result is a gallery grounded in artists’ advocacy, toi Māori engagement, and boundless potential.

We sat down with Peggy to discuss all that PEG entails—who Peggy is, her relationship to the arts, and her aspirations for this new venture.

Tell us about yourself. Who is Peggy?

I’m 29 years old, I grew up in Ōtautahi, and studied in Tāmaki Makarau at Elam School of Fine Arts. I moved to Pōneke with my partner in 2018. I’m a middle child with two brothers, a Capricorn, an introvert and a bad sleeper. I eat lemons like oranges, have hairy legs, love to swim in cold bodies of water and consume vastly more than the recommended dietary intake of sodium.

I’ve worked within the visual arts in Aotearoa for a decade, most recently spending seven years with Page Galleries in Pōneke. This mahi has been deeply rich and joyful — working closely with artists and supporting their practices. I’ve come to see my role as one of advocacy: for artists, and through them, for the ideas and conversations that art can bring into being. I’ve always been drawn to the connective and storytelling power of art, how it creates shared spaces of thought, feeling, and exchange.

Who is Peg in relation to Peggy?

PEG is inevitably an extension of myself. We all act from within our own perspectives and biases. So the decision to name the gallery PEG came from a place of acceptance. An acknowledgement that this project carries my voice and sensibility, while also creating a platform that belongs to many.

I hope to be a foundation rather than a figurehead. PEG will be a place where artists and their communities can take the lead, and where collaboration and exchange are central to how the gallery operates.

I feel like every aesthete has experienced ‘one work’ or ‘one show’ that set alight their passion for the arts. What is yours?

When I was little, my father and I would spend Saturday mornings roaming through the Christchurch Arts Centre — eating hot noodles, smelling the honey-roasted peanuts, and perusing the stalls — before visiting Christchurch Art Gallery to see our favourite paintings. Dad would always lead us to the Hoteres. I remember standing before those vast black works, completely dwarfed by them, while he explained ideas from te ao Māori: that blackness, Te Pō, is not an absence or darkness, but a realm of potential and becoming.

Those experiences shaped how I understand art, as something expansive, layered, and alive with possibility, but also as something that can inform and shape our daily experience of the world. Art doesn’t need to exist apart from life; it enriches it, quietly prodding at how we see, feel, and relate to what’s around us.

What qualities in an artwork or series are you most drawn to? What are you most excited about exploring in-show at Peg?

I’m drawn to works that reveal a sustained curiosity and through which you can see the artist’s mind at work. I tend to be personally biased towards works that are storytelling, thinking about how we all digest information so differently and how art has such a unique power to convey meaning; to bring people into kōrero and to perhaps reveal new ways of thinking about or understanding a concept. I’m especially interested in exhibitions that open space for exchange — intergenerational conversations, cultural crossings, or material and conceptual collaborations.

At Peg, I’m excited to create environments where these dialogues can unfold naturally, and where the gallery becomes a meeting place between artists, ideas, and audiences.

After a seven-year tenure at Page Gallery, what have you gleaned about Pōneke’s taste? Do you find the region has carved out a distinct visual culture?

Pōneke has a very particular energy — thoughtful, grounded, and deeply community-minded. It’s a windy coastal city, and I think the environment fortifies you; those who choose to live here tend to be warm, resilient people, and this whenua demands that of you.

It’s also a city brimming with creativity, home to both artists and civil servants, thinkers and makers. You can feel that balance in the art here: conceptually sharp, politically aware, but always human and connected to place. The galleries in Wellington work with a spirit of collegiality, what’s good for one is good for the whole, and the collectors reflect that too. People here buy with love and conviction, not to complete an image of a collection, but because a work genuinely moves them.

Your inaugural exhibition featured a series of works by Reece King, Halfway to the Splits. Tell us about your decision to host King as your first artist.

Reece’s work embodies a rare combination of intellect and instinct. His approach to painting is physical, searching, and precise. He is always evolving and questioning, but often does so through a very playful joyful visual language. Beginning PEG’s programme with Halfway to the Splits felt right because Reece’s practice speaks to the kind of depth and inquiry I hope to nurture within the gallery.

Reece is also at a really exciting point in his journey, with his move to Ōtepoti for the Frances Hodgkins Fellowship and this being his first outing in Pōneke. It’s a wonderful time to introduce people here to his mahi. His presence sets a tone of trust, curiosity, and ambition for what’s to come.

Opening your own gallery space, or any commercial endeavour for that matter, commands a certain level of self-assuredness. What is the most valuable thing you have learned about yourself and your practice throughout this process?

This has been in my dream journal for a very long time, but there was a pivotal moment when I realised that with committed planning, I could viablely and sustainably make a gallery work — that I could build something around the values I hold. Since then, I’ve been slowly chipping away, extrapolating the idea into a reality.

Commercial galleries are unique in that, unlike large public institutions, the people who run them share a kind of kinship with artists in the risk they take on. There’s fear in that, but also deep purpose. It takes a village to make something like this happen, and I’m incredibly lucky to have a pretty special one.

The Gallery, as a format of exhibition, has been this arbitrating fixture of the European art tradition for centuries now. Gallery direction and Curatorship are immensely powerful in their capacity to broaden the scope through which the viewer experiences art—are there any facets of the traditional gallery that Peg aims to challenge, particularly in relation to your commitment to embracing Kaupapa Māori?

I believe that commercial galleries have the potential to be porous and responsive to the needs of their communities. PEG’s kaupapa is grounded in manaakitanga and whanaungatanga — care, generosity and relationships. Rather than thinking in terms of representation, I have been working on a framework of te raranga pū toi — the weaving of creative relationships. This approach acknowledges artists as partners and allows the gallery model to shift and shape around their needs. It lends itself to an exhibition-led approach, where with each exhibition the gallery's energy can shift, grow and shrink to ensure it is holding the artists and their mahi appropriately.

As tangata Tiriti, I’m committed to the responsibilities and privileges that come with working in the arts in Aotearoa — supporting Māori artists, creating opportunities for toi Māori to shine, and fostering meaningful engagement with toi Māori and te ao Māori. Our understanding of the world around us, and the whenua we occupy, is deeply enriched by the expansiveness of Indigenous knowledge and artmaking. In opening PEG, it was important that the space was led by kaupapa Māori from the outset — the gallery was blessed in a whakawātea led by mana whenua, Taranaki Whānui, acknowledging and grounding the work that will take place within it.

If you could distill your curatorial philosophy in one word, what would it be and why?

Exchange. Art is a site of continual exchange; of ideas, care, trust, and challenge. It’s a kōrero that moves in multiple directions.

Lastly, what are your base aspirations for Peg in its collaboration with Pōneke’s contemporary artists?

At its heart, PEG aims to create meaningful opportunities for artists — both creatively and materially. I want it to function as a site of experimentation and trust; a place where artists feel supported to take risks, and where audiences feel genuinely welcomed into that process.

If PEG can contribute to sustaining diverse voices and practices in Pōneke and offer a space where people feel seen, safe, nourished, and inspired, then it will have achieved its purpose.

Reece King’s ‘Halfway to the Splits’ runs from November 1st - 29th at PEG Gallery.